Ukiyo-e is an art-form that has enamoured people for centuries since its first inception in the Edo period (1603-1867) in Japan. Often translated as “pictures of the floating (or sorrowful) world” it is considered to be Japan’s original pop art, because of its functional role of the times, serving the roles of fashion photographs, celebrity stills, and travel guidebooks, catching the mood of the era and depicting daily life.

The printmaking process from artistic creation to finished product typically required four distinct parties to be involved:

1. Hanmoto, the Publisher

Akin to modern day book publishers, the overall production of Ukiyo-e prints was coordinated and overseen by the hanmoto, who made the decision as to what style of art to commission, which artists to employ, and which final format the pieces should take. In their hands was the necessary power and acumen to promote the rise or emerging talent.

1. Eshi, the Artist

The eshi received a commission by the hanmoto to produce a drawing (hanshita-e), usually in black ink. The woodcarver would then use the hanshita-e to cut the key block of wood (omohan). At this stage the artist would specify the remaining colours to be used in the piece, and after reviewing various sample prints deliberate on any final changes and adjustments to be made. Ukiyo-e artists were required to achieve the final result within a limited number of pressings, which meant that a minimalistic attitude in design was needed to be undertaken in order to guarantee a successful pressing process.

1. Horishi, the Woodcarver

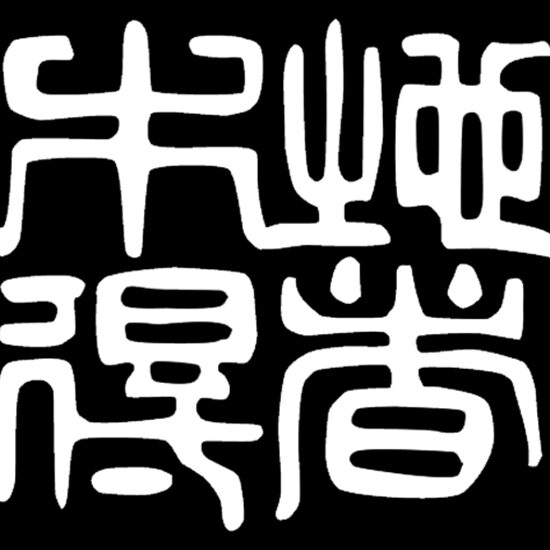

The horishi would place the drawing face down on a block of cherry wood and proceed to carve out the reversed picture using a variety of chisels and fine knives. On completion of the key block he would continue and carve out a series of color blocks (irohan). The skill of the carver determined the precision with which details such as fine rain or strands of hair were executed and turned out on the final print.

1. Surishi, the Printer

The surishi would impress the image onto hand-made washi paper. The number of pressings would vary from one piece to another. First in line was the key block, and then the colour blocks with smaller printing surfaces followed by those with larger ones. Generally, lighter colour preceded darker ones. The printer’s skill was greatly put to the test when executing hand-shaded gradations.

In conclusion, Ukiyo-e making was, and is, a collaborative effort that required as many as four parts to see its completion. Many artists are still faithful to this process, one to which I do not ascribe, partly because it is impossible physically for me to do so, but mostly because my methods are too distant in nature from the traditional ones. Albeit, I have a deep appreciation for the traditional way and hope that it keeps on staying strong into the impending future.

*texts retrieved in part from the Kateigaho International, Japan edition. vol.38 Autumn/Winter 2016